Source attribution study findings, part 1

Trust is shaped not just by the presence of solid sources but by how those sources are framed

I’ve been working on a study for what feels like ages now, and I’m still trying to process the unexpected complexity of it all.

The initial premise seemed straightforward: I set out to explore how different methods of source attribution influence a reader’s trust in an article. But as with most things, the devil is in the details. Designing and analyzing the study turned out to be far more challenging (and far from perfect) than I imagined. There are simply too many variables to account for, and as much as I tried to control them, it felt like some always slipped through the cracks.

The experiment itself was built around three different versions of an article based on a real scientific study—one that examined the impact of air pollutants on pollinators' ability to find flowers. Each article used a different form of source attribution: one cited the university hosting the research and included direct quotes from the researcher; the second summarized the research findings in detail and referenced the university; and the third attributed the information to nothing at all.

I began by collecting basic demographic data, followed by a brief quiz to measure participants' general scientific literacy (this was to assess whether background knowledge had any effect on how they perceived trustworthiness). Then, each participant read one version of the article, followed by a quick questionnaire on article trust and some open-ended responses.

I expected that the article with direct quotes from a researcher and a university would be the most trusted, the one with no attribution at all would be the least, and the version with a summary would fall somewhere in between. But the results were far from what I had anticipated.

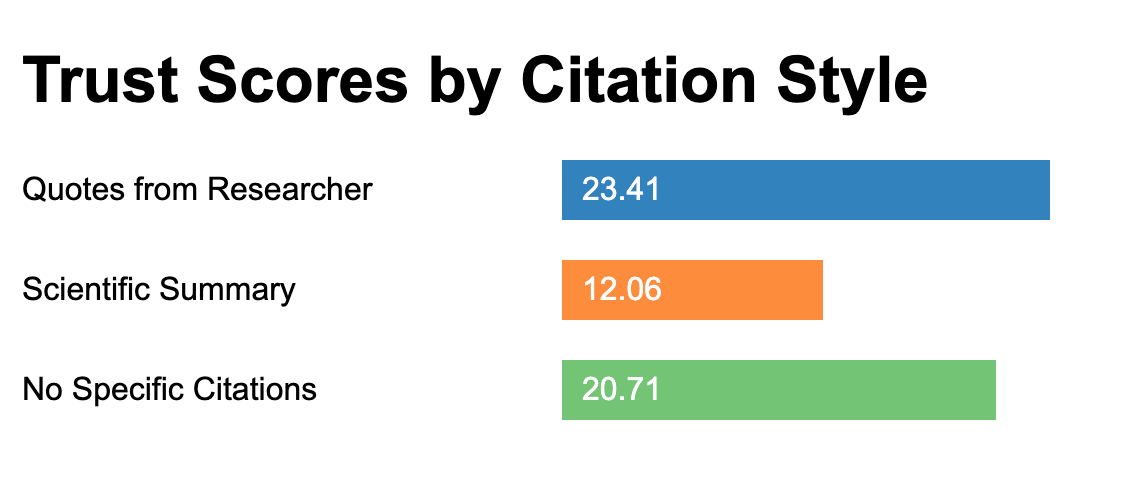

The articles that included direct quotes from a researcher with a university cited garnered the highest trust scores—an average of 23.41. This indicated a relatively strong sense of trust among readers. On the other hand, the article with no citations at all still managed an average score of 20.71, which suggested a moderate level of trust despite the lack of formal attribution.

The real surprise, however, came from the article that included a summary of the research but still referenced both the researcher and the university. It had the lowest trust score: 12.06.

This was, to say the least, perplexing. After some reflection, my hypothesis began to take shape: while formal sourcing undoubtedly adds credibility, it may also alienate readers by creating a sense of formality or detachment. Some more-detailed citations could have come across as a barrier, making the information feel more distant or academic. In contrast, the articles without formal attribution seemed to present the information as more neutral, approachable, and free from institutional influence—despite the clear potential for reduced academic rigor.

Ultimately, the results underscore the critical takeaway that trust is shaped not just by the presence of solid sources but by how those sources are framed. A study’s findings may be more credible when they’re presented transparently, but too much formality can hinder engagement. Meanwhile, articles that forgo attribution can feel more straightforward and less entangled in the complexities of institutional authority. The real challenge, then, lies in finding the sweet spot—a balance between rigorous sourcing and an accessible, reader-friendly presentation.

These findings are still a work in progress, but they’ve certainly shifted my thinking.

More insights to come.